- Home

- Eva Crocker

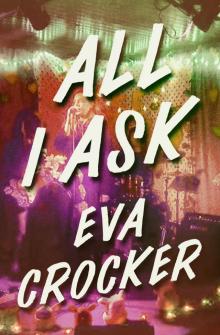

All I Ask

All I Ask Read online

Also by Eva Crocker

Barrelling Forward

Copyright © 2020 Eva Crocker

Published in Canada in 2020 by House of Anansi Press Inc.

www.houseofanansi.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

All of the events and characters in this book are fictitious, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Title: All I ask / Eva Crocker.

Names: Crocker, Eva, author.

Identifiers: Canadiana (print) 20190165464 | Canadiana (ebook) 20190165480 | ISBN 9781487006075 (softcover) | ISBN 9781487006082 (EPUB) | ISBN 9781487006099 (Kindle)

Classification: LCC PS8605.R62 A75 2020 | DDC C813/.6—dc23

Book design: Alysia Shewchuk

We acknowledge for their financial support of our publishing program the Canada Council for the Arts, the Ontario Arts Council, and the Government of Canada.

For Jess Gibson

one

They took my computer and phone so they could copy the contents. They called it a mirror image. They said it was the fastest way to prove I wasn’t the suspect and also I didn’t have a choice.

There were nudes, there was a picture, taken with the flash, of a pimple on the back of my neck — swollen and inflamed. They didn’t know when they’d get to it. The unit was really backed up. What was it called? Child Pornography? Digital Something? “The Unit.” He said there were only three or four guys in the Unit. For the whole province.

There were emails back and forth with my mother, scheduling visits with my grandmother in the hospital. Emails where I said things like, I have kickboxing but I guess I can go in if no one else is available — lessons are prepaid. There were rejection emails from casting directors.

All the stupid things I’d googled. Things I should have known. When did Newfoundland join Canada? What is Brexit? Are most oven dials Fahrenheit or Celsius? How much of that is in the mirror image? Reams of it.

These things take time. Couldn’t tell you. A judge in Gander had signed the warrant. What were they looking for? Illegal digital material. What does that mean? And what does “transmitted” mean? Transmitted from my address. Is it the same as seeded? It’s different than uploaded, I’ve seen “uploaded” in the paper. Footage of a slump-shouldered man with a windbreaker pulled over his head walking into the courtroom. A drawing in the newspaper of some sad-sack, evil piece of shit sitting beside the judge.

Who was combing through my hard drive? Picking through the digital traces, footsteps, shadows. Taking in all the un-deleted drafts, all the weird, unflattering angles. Three or four guys, taking their time.

* * *

When they came to my house, my hair was greasy and I wasn’t wearing a bra. I’d slept on my ponytail, it was sagging at the base of my neck, and I had glasses on. Normally I wear contacts; the glasses are an old prescription. I can’t read street signs with them. I’d slept in a big T-shirt and a pair of bicycle shorts — no bra. I woke up to the doorbell ringing and a pounding that shook the house. Both at the same time — the doorbell and the knocking. It woke me up. I put my glasses on and went to look out the window. The plastic frames were cold on the bridge of my nose, it made my sinuses tingle. Someone was pressing the doorbell in and holding it down. I pulled the curtain open with one hand and leaned out of view.

I assumed the knocking and the doorbell was someone wandered up from downtown. When you live downtown belligerent people wander up. They yell and piss in the street and sometimes they ring your doorbell again and again. You turn off the lights and wait for them to go away.

The month before, my roommate Holly and I had moved into a house at the end of a short street. Our living room windows were street level and looked onto a small parking lot on the side of a church. A nurses’ union and a row of group homes backed onto the lot, hiding it from the main road. The front of our house and the church enclosed the parking lot.

The top floor of the church had recently been turned into eleven bachelor apartments for low-income tenants. A clutch of people were always smoking near the church’s side entrance, facing the house, or else on the fire escape that extended from the church’s second floor. I left the curtains open and the living room lights brazenly bright in the evenings, even though you could see right in.

The church owned a dumpster that sat in the parking lot. Sometimes I’d slip into rubber boots and cross the parking lot with a garbage bag. I’d wear just my fleece bathrobe over a T-shirt and shorts when I ran out. The opening in the side of the dumpster screeched when I tugged on the handle. On cold days the side opening froze shut and I’d have to get on tiptoe and lift the dumpster’s lid with one arm to heft a bag of garbage in. The unlocked dumpster felt like a luxury, to be able to rid yourself of anything whenever you wanted.

There were two windows in my bedroom; one looked onto the parking lot in front of the house and one looked onto the back of the church. Behind the church there was a yard surrounded by a chain-link fence with sign that said “Outdoor Play Area.” There had been a daycare in the building long before we moved in. Now neighbourhood cats squirmed between the locked gates and used the Outdoor Play Area as a litter box. The shiny tape from inside a VHS was tangled in the branches of a tree just outside the fence. From my bedroom I could see the black ribbon moving in the wind, the plastic case knocking against the tree’s trunk.

Each time they pounded on the door, the crystal light-catcher I’d stuck to the window with a licked suction cup tapped the glass. I couldn’t see who was on the step so I had to lean into the window. Four cops. Only two could fit on the step, the other two were standing below them on the sidewalk. One had a shiny bald head. I thought there must be a fire next door. I was thinking that fire-drill word, “evacuate.” There must be a reason I need to evacuate. To be evacuated.

I opened the front door a crack and the bald cop put a hand on the door frame.

“We have a warrant,” he said.

“What?” I said.

“Move out of the way, we’re coming in, we have a warrant.”

“Why? For what?” I held the door.

“You’re going to have to move out of the way,” the bald cop repeated.

“Why?”

“Because we have a warrant,” he said. “Move out of the way.”

“But why?” As I was saying it, I stepped backwards and let the door fan open. The bald cop walked past me into the house. The other three men crowded into the porch, leaving the door ajar behind them.

“The animals,” I said, backing into the living room. “Don’t let the animals out.”

The three backup cops followed me into the house. Salty boots on the floor.

“What’s down here?” one cop asked, opening the door to the basement. “Is there a light?”

There was a parade of white-and-blue cop cars in front of the house. I looked out at the parking lot. Three regular silver cars with cops inside were pulled up next to the dumpster.

The woman who always sat on the church’s fire escape stairs — I could hear her coughing out there all night long — was on the bottom step, sneakers in the slush. The man who sometimes accompanied her was hunched on the step above her, a travel mug between his knees. Because of the out-of-date prescription in my glasses their faces were just pale smears above their collars. I thought they must be able to see the swarm of cops inside the house. Were they sympat

hetic? Worried about me?

“The cats,” I said. “Please.”

The last cop turned around and batted the front door shut.

“You have to lock it, it blows open,” I said.

He paused before turning the deadbolt, deciding how much of an asshole to be, then walked into the kitchen and started opening the cupboards. The bald cop stood in front of me, legs wide apart. The cop who’d asked about the light made his way down to the dark basement, the fourth clomped upstairs in his heavy boots. Something fell in the kitchen, something plastic that bounced, I couldn’t think what it might be.

“My roommate is in bed,” I said, realizing. “Don’t scare her.”

“Is there a light down here?” the cop called from the basement.

“We have a warrant for the transmission of illegal digital material,” the bald cop said.

“She’s asleep, don’t scare her.” My voice came out loud but trembly. I saw the cop on the stairs hesitate before continuing up towards the bedrooms.

“Who’s your roommate?” the bald cop asked.

“She’s in bed.” I felt the muscles in my thighs shaking like I’d just finished a long bike ride.

“What’s her name?” the bald cop asked.

“Holly,” I said.

The cop who’d been digging through the kitchen came back.

“Last name?” the bald cop asked. “Take a seat, sit on the couch.”

“Holly Deveraux.” I sank into the couch.

“What’s your name?” the bald cop asked.

“Stacey Power.”

“Do you know Natalie Swanson?”

“She lived here before us, I don’t know her. We just moved in,” I said.

Their faces changed. The bald man beckoned and three more cops came through the back door into the kitchen. How long had they been out there, waiting between our snow-covered bikes and the rusted-out barbeque? The last one shut the door behind him. The cats crouched amongst the cops’ boots, tails wrapped around themselves, bellies close to the floor. Their heads jerked back and forth on scrunched necks as they took in all the strange people.

“There’s no one up here,” a cop called from upstairs.

“She must have stayed at her partner’s,” I said.

I was trying to count how many men were in the room but they all looked the same and they were moving around. Were they wearing guns? Yes. Also those extendable sticks for beating people.

“Her what?” the bald cop asked.

“The person she’s seeing,” I said.

“What’s his name?”

“I don’t know — I don’t really know who she’s seeing.”

“You don’t know his first name?”

“We just moved in here, on November first,” I said, hoping to summon the uncertainty I’d seen on his face when I told him I didn’t know Natalie Swanson.

The bald cop looked at the cop beside him, a guy my age. The look suggested there had been a fuck-up and someone other than the bald cop was responsible for it.

“November first,” the bald cop said, deflating. “Well, I’m going to need to see some ID and the lease.”

Two cops let themselves out and stood on the front step. One of them squeezed the sides of a walkie-talkie on his shoulder and muttered into it as he left.

“The door will blow open,” I said. “The cats.”

“Those guys are coming right back,” the bald cop said.

The young cop followed me into the kitchen. I dug around in the drawers; the lease had slipped down into a pile of kitchen junk the previous tenants had left behind. Beaters and fondue forks and blades for a long-lost blender. It was a carbon copy of the lease we’d signed; the landlord had taken the original when he gave us the keys. The thin pages were scrunched up and not in the right order. I found the sheet with our signatures and the date in faint grey handwriting and held it out to him.

“Got the lease here,” the young cop called.

It was the young cop who followed me up to my bedroom to find my driver’s licence. The two geraniums on my windowsill were in bloom: the petals on one plant were a deep, bloody red; the flowers on the other were searing fuchsia.

I had a cold, there were used tissues scattered around the bed. A roll of toilet paper on its side by my pillow had unrolled, leaving three clean squares flat against the floor.

“I have to follow you up here,” the young cop said, taking in the unmade bed and phlegm-stained tissues.

I picked my winter jacket off the floor, the straps of my book bag were still tangled in the coat’s armpits. I pulled my wallet out of the pocket and let the coat-knapsack jumble smack against the floor. I flicked through the receipts, movie tickets, and download cards for friends’ albums. I saw the tiny, washed-out picture of myself. The young cop looked at my ID, then handed it back to me.

“Bring that downstairs and we’ll show it to Sergeant Hamlyn,” he said.

His boots were loud on the stairs but I could feel him giving me space, waiting for me to get two paces ahead before thudding down behind me.

“Got some ID there?” the bald cop asked.

The young cop nodded and I held the card out.

“We’re going through with the search. We’ll all be as respectful as possible,” the bald cop said to the room.

“I’m going to read you the warrant,” the young cop said, sitting at the kitchen table and pulling out a chair. “Just take a seat.”

He was holding a couple of printed pages with something like a business card stapled to the top left corner. The other cops spread out, opening doors, tossing the couch cushions on the floor. I heard a crash from the bathroom; one of them must have opened the mirrored cabinet and all the makeup Holly had crammed onto the top of the case had fallen into the sink.

“Whereas it appears on the oath of —” the young cop began.

“You don’t have to read it to me,” I said.

“I have to read it to you,” he said. “Take a seat.”

* * *

When they finally left I went upstairs and put in my contacts. It felt like stepping out of the blurry chaos of the morning. I stood at the window watching the cops climb into their cars and leave the parking lot. They took my computer and cell phone but left a handful of flash drives — filled with old photos, papers I’d written in university, papers I’d edited for friends. They told me the flash drives were “cleared at the scene.” They took an external hard drive from Holly’s room, a slim silver rectangle with a thick cord wrapped around it. There was no way to text Holly and tell her what had happened.

She’d been sleeping somewhere else occasionally, maybe at Dave King’s — she didn’t talk to me about who she hooked up with. The cops had been in her bedroom, stripped the bed, lifted the mattress, gone through her drawers. I wanted to tell her in person.

One unmarked car lingered on the other side of the parking lot. Inside, a cop was touching a computer screen attached to the dashboard. Above his car, the sun was catching on the VHS innards snarled in the tree. The light made greasy rainbows on the tape as it stretched and drooped in the breeze.

* * *

Months before the cops stormed our house, the plywood barrier that runs along Duckworth Street hiding an inactive construction site was spray-painted ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE. FUCK THE POLICE. The painter had held the can close to the plywood so the tall white letters dripped down the wall. The doors of the courthouse were covered in smashed eggs; yolks hardened on the wood and cracked shells littered the threshold.

The night before, a cop, Officer Doug Snelgrove, had been found not guilty of sexually assaulting a young woman he’d driven home in his cruiser. On the stand, he said he’d known she was drunk; he said that he had sex with her while he was on duty, while he was in uniform with a gun attached to his pants. The story was in the

news for weeks. He admitted that he’d radioed in every other ride that night but not that one. He said he’d smelled alcohol on her breath but he didn’t realize she was too drunk to consent, even though as a cop he was trained to recognize drunkenness, even though he’d testified about impairment at drunk driving trials. She told the courtroom she’d blacked out. She’d asked a cop for a ride home because she was too drunk to get home on her own. The woman’s friend testified that she’d called him just before the incident happened and she’d been incoherent on the phone.

Snelgrove was more than a decade older and he’d been stone-cold sober.

The night the Snelgrove verdict was announced, people gathered outside the courthouse and howled “No justice, no peace” into loudspeakers pointed at the sky. The following day people stopped each other in the street to ask if they’d heard about the verdict, eyes glossy with tears, jaws clamped with rage. People asked, “Are you sure? Who told you? You actually saw the article? Who published it?” And then they said, “An appeal. There has to be an appeal. Did it say anything about an appeal?”

The bleak reality of the verdict settled on the city. Someone printed stickers that said “Hell No Snelgrove” and pasted them on parking meters and mailboxes. I passed ABUSE OF POWER COMES AS NO SURPRISE. FUCK THE POLICE. on my way to work and when I went to bars to hear music. Then there was the pounding that shook my house, four cops on my doorstep, more hiding outside the back door.

Two

Everyone wanted to be Holly’s friend when she first got here — she had so clearly just arrived from a big city. Everyone wanted to show her around. To have some of her fashion sense rub off on them. To wow her with a sweaty hike up to Soldier’s Pond where you can take in Signal Hill from the opposite side of the harbour and swim in your underwear. To maybe make out with her because (if you grew up in St. John’s and still live here) it’s not that often you get to make out with someone you haven’t known since eighth grade.

All I Ask

All I Ask